The Old Testament Language Gap

- Nathan Schneider

May 17, 2008 was a big day for me. It was the day I left the label “bachelor” behind and entered the domain of marriage, never to look back. Everything about that day was exciting. Natasha and I spent the first half of the day apart, ironically, but the nervous butterflies freely flapped their wings around my insides as I nervously waited for the hour to arrive. The moment my bride appeared in the doorway of the little baptist church in North Pole, AK (yes, we were married at the north pole…sort of) and began her slow walk down the center aisle, the whole room went away and it was just her and I.

I remember some of the ceremony. I think I remember what the pastor said. I know he gave us some humorous gifts to illustrate how we should look at our roles in this new life we were making together. I distinctly remember putting on rubber kitchen gloves in front of the congregation (to illustrate how I should serve my wife). But you know what I remember most about that ceremony? The kiss. It was the kiss that marked us as a man and a wife, joined together in a spiritual bond by the wisdom and power of God himself.

Now, my wife wasn’t wearing a veil that day. It seems like bridal veils are becoming less and less popular in contemporary bridal style. But let’s assume for a moment that she had been wearing one. The moment the pastor pronounced us as husband and wife and invited us to take that first kiss of marriage, imagine if I had gone straight in to that kiss without first lifting off that veil. Would it have been any different than removing the veil first? Would I not be kissing the same person if the veil were up? Why would it matter one way or another?

Well, you know the answer. It does matter. Yes, she’s still the same person, but the veil acts as a slight barrier between her and I, making the experience less than it could be.

The Jewish poet Haim Nacham Bialik likened this scenario to what it’s like when a person reads the Bible by means of a translation: “Reading the Bible in translation is like kissing your bride through a veil.” Yes, it’s still the same truth behind that veil, but there’s a distance between us and the text as a result of approaching the Bible through a translation. We refer to this distance as the language gap.

Reacting to the language gap

Now, there’s a few reactions we could have to this language gap, but for the sake of simplicity, I’m just going to cover four of them. The first two we might say are the “extreme” reactions. The second two are more reasonable responses. Obviously, we’re going to zero in on the latter two as the desirable type of responses we should aim for in all of this!

Extreme Reactions

I suppose one reaction we could have would be to simply deny that the language gap exists. That is to say, we could simply stand on the ground that it doesn’t matter that the Bible (and the OT in our case) was written in a different language. It’s written in English now, and obviously English is God’s language because it’s the language of America!

Let me just say, this position is fraught with issues. First, it assumes that there’s such a thing as a perfect translation. Well, if there is, we haven’t arrived there yet or else we wouldn’t have all the various translations out there. It’s impossible to know for sure how many English Bible translations have been produced over the years, but some have estimated there to be about 900 official English translations of the Bible, with new ones still in the works. I hate to break it to you, but there’s always going to be a better way to translate something from one language into another, either because our language changes, or because our knowledge of the original languages improves with new linguistic discoveries.

On the other extreme, we could react by going into complete panic. We could start to hyperventilate at the thought that if we have to read a translation of the Bible, then can we really ever be certain what the Bible says? This reaction assumes that the only person who can really know God’s Word is the one who can read it in its original language.

This reaction is equally tenuous and unreasonable. Obviously, no one holds this hard-line approach outside of biblical discussions. If you’ve ever watched the Olympics or tuned into C-SPAN (this is all just hypothetical, we know no one watches that), you know that not everyone speaks the same language, and when we hear an English translation of whatever the German guy is saying in the meeting, or when we hear an English translation of what Vladimir Putin just said to Donald Trump, we don’t really freak out and ask, “But can we ever really know what he said?” We simply take the translation as a given.

But there are some who panic at the notion that their English Bible might not be the perfect translations they need it to be. We want to avoid denying the existence of the language gap as well as panicking over it. Both are extreme reactions that don’t help anything and can actually be a tool the enemy can use to get you to doubt truth and doubt your faith.

Reasonable Responses

There are better responses we can have to the idea of the language gap. They’re moderate and reasonable, although even here I have my bias as to which one I’d suggest you take.

First, we could simply say, “I recognize that there is a language gap. I accept this as a fact, and I accept that accessing the Bible through a translation will always mean that there’s at least some distance between myself and the real text of Scripture.” Now, on the surface, that seems like the right response to have. We’re not denying the gap exists, nor are we panicking over it. We’re simply accepting it as reality and moving on with our lives. But what does it mean to “move on with our lives”? In this case, it means you simply pick the translation you want to use and you decide that you’re going to entrust yourself to the translational skills of the people who made it. And when it comes to Bible study, I’ll listen to my pastor, or maybe I’ll read a devotional commentary, but I’m content not to wade into the details.

But I think there’s a better way. What if we take the first part of that response–the part where we accept that the language gap exists–but then rather than being fatalistic about it, we become proactive about it. What if we say, “I don’t need to learn Hebrew and Aramaic in order to read the OT, but I can still do something about bridging this gap”? Believe it or not, you don’t have to be a pawn in the world of Bible translation. You can be as active or as passive as you’d like in this process. It doesn’t mean you have to go take a class in Biblical Hebrew. It simply means getting proactive with your Bible study so you know what the issues are in translation and how to try to bridge them.

Bridging the Language Gap

There’s plenty of good books that have been written on the topic of Bible study and interpretation. Some of them get pretty technical and are aimed toward scholars, pastors, and seminary students. But others are written specifically for the layperson who wants to know how to study the Bible for himself or herself. It’s not my goal to give you a full explanation of how to do self-led Bible study (but I’ve listed some recommended books on the subject at the end of this post). My goal here is to help you understand how you can be proactive in your Bible study in bridging the language gap without having the learn the biblical languages for yourself. You can still rely on others to translate the text, but your level of reliance and independence is completely up to you.

Read Good Translations

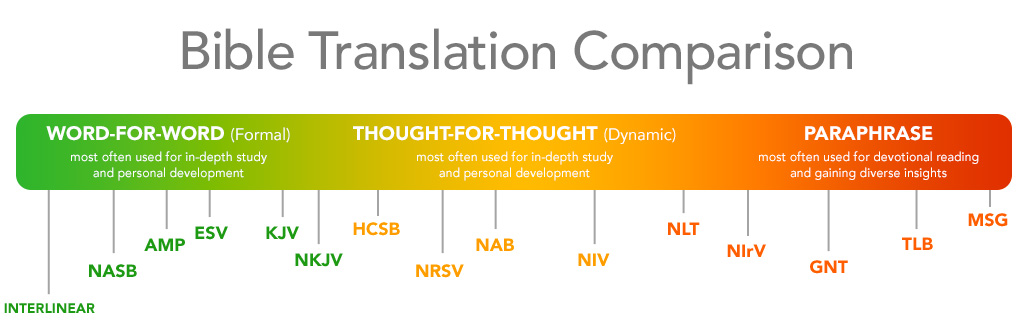

Believe it or not, there are good translations of the Bible and there are bad translations. Not all translations are equal, and a lot depends on the philosophy of translation used to produce the version in question. Basically, there’s two schools of thought on Bible translations. The first type of translation is called formal equivalence, which refers to a principle of translation by which the translator(s) attempt to stay as close as possible to the structure and words of the source language. These translations are often referred to as “word-for-word” or “literal” translations, although both of these labels aren’t exactly accurate or desirable. In their book Grasping God’s Word, J. Scott Duvall and J. Daniel Hays write, “Translators using this approach feel a keen responsibility to reproduce the forms of the original Greek and Hebrew whenever possible. The NASB, HCSB, and ESV use this approach. On the downside, the formal approach is less sensitive to the receptor language of the contemporary reader and, as a result, may appear stilted or awkward. Formal translations run the risk of sacrificing meaning for the sake of maintaining form” Duvall and Hays, Grasping God’s Word, 35).

The second type of translations is called dynamic equivalence, and refers to a translation principle by which the translator(s) attempt to express the meaning of the original in the receptor language (in our case, English). These translations are often referred to as “though-for-thought” or “functional” translations. Again, Duvall and Hays comment, “Here the translator feels the responsibility to reproduce the meaning of the original text in English so that the effect on today’s reader is equivalent to the effect on the ancient reader. Many contemporary translations utilize this approach, including the NLT and GNB. The functional approach is not always as sensitive as it should be the wording and structure of the source language. When it moves too far away from the form of the source language, the functional approach runs the risk of distorting the true meaning of the text” (ibid.).

Now, there’s a third category of translations which could be called “paraphrases,” but in actuality they’re more like concise commentaries than actual translations, so we’ll leave them out of the discussion (e.g., The Message, Living Bible, Amplified Bible, etc.).

Now, when it comes to choosing a good Bible translations, there’s two extremes we want to avoid. First, we want to avoid the attitude that says, “Eh, they’re all good! Just pick one!” There’s been too much ink spilt over this subject to come to that conclusion. Some translations are certainly better than others. We also want to avoid the other extreme, where we say, “Only my particular translation is acceptable.” This is, obviously, a common stance taken by those who advocate that only the King James version is acceptable for use, but there are plenty of others who look down and judge other Christians based on what translation they use. And while I reiterate that not all translations are created equal, neither can we say that one translation is the only acceptable version.

But because we’re dealing with bridging the language gap of the Bible, there’s a clear winner when it comes to choosing a translation. Since dynamic equivalent translations specifically try to capture the meaning of the text and care less about preserving the structure and individual words, these kinds of translations are clearly less suitable for going about studying the Bible on your own. This is not to say you can’t pick up your NIV or NLT Bible and read it on your own. But when your goal is the get as close as you can to the original language as possible, you need to rely on versions whose philosophy of translation is designed to preserve wherever possible the structure of the original language. That means sticking to formal equivalent translations.

Tried and true formal equivalent translations include the 1995 update of the New American Standard (NASB95), the English Standard Version (ESV), as well as the King James (KJV) and New King James (NKJV), although the latter two present challenges when studying the NT because of their less-reliable textual base.

In addition to these staples, you could add the New English Translation (NET), which isn’t exactly a formal equivalent translation, but it comes with copious textual, syntactical, and theological notes (a lot like a study Bible, but different) explaining why translation decisions were made as well as discussing key translational challenges as they arise.

If you want to get as close as you can to the original language text without learning it for yourself, then pick yourself up an interlinear Bible. These Bibles have the Hebrew and Greek text of the Bible with an English translation written below or next to it. Many of these are available in NASB or ESV and are very helpful tools for seeing the original text alongside a reliable English translation.

Read Several Translations

When you read a single translation of the Bible, even a formal equivalent translation, you’re encountering the translational decisions of one particular translator or translation team. That means you may not be able to tell when there may be other ways to translate a given passage, or when there are certain issues present in the original language that make it challenging to translate into another language. But you can get a better sense of these challenges by not using just one but several translations of the Bible when you go to study it for yourself.

This doesn’t mean you have to study out of multiple translations. When you’re doing your primary study (observation), use one translation. It just means that when you’re starting to look at a passage, one of the first things you can do is see if there are some major differences in the way other translations render the passage. We’re not talking about one or two words being different synonyms. We’re talking about major differences, such as the order of words and phrases, or how many words it took the translators to express the idea of the original text. Often times, big differences between versions will signal that there’s a translational difficulty in the original text. You can then note that issue and explore it by seeing what a commentary has to say.

Do Good Word Studies

One of most fundamental inductive Bible study skills you can have is being able to do a word study. Now, in order to do this, you have to be able to use a few study tools, such as an exhaustive concordance and a theological dictionary. But rather than taking you through the process of doing a word study, which you can learn from the books I link to at the end of this post, I want to talk about some bigger picture issues when it comes to studying words in the Bible.

Words are the smallest unit of language and they serve as building blocks. How they are arranged together into phrases, clauses, sentences, and how the syntax and grammar of the language works, determines how these words interact with each other to communicate meaning.

Now, there’s a few rules of thumb to know about when it comes to doing a word study.

Not every word needs a word study

There are actually far fewer words that have a very special, significant impact on the meaning of a text in and of themselves. We might call these words “goldmines” of meaning, and they’re not as common as you might think. One such word in Hebrew is hesed, which is often translated as “lovingkindness,” but in actuality is a word that speaks of love or mercy that is based on God’s covenant commitment to his people. It is love that is fiercely loyal because it is founded upon God’s loyalty to his covenant. While there are these type of words in the OT and NT languages, far more often the significance of a word is not in the word itself but how it’s used in the passage.

Not every word means the same thing all the time

Words have backgrounds. They had to start somewhere. Just like our English word “dynamite” originates from the Greek word dunamis, meaning “might” or “power,” so Hebrew and Greek words have an origin. But we have to be careful that we don’t assume that any particular word carries the same meaning it did when it was first used. Meaning changes over time. Just because a word originally meant one thing doesn’t mean that it always means that every time the word pops up in your Bible.

Similarly, words can carry a range of meanings. Our English word “trunk” is a clear example. How many different meanings does this word have? Moreover, how does one determine which meaning was intended by the author?

Context is the driving force of the meaning of a word

Obviously, words are important. You can’t communicate linguistically without them. But one of the key realities to keep in mind is that the meaning of a word and its significance is determined ultimately by the context and not by the word itself. Take for instance 1 Samual 15:22–23, which reads,

Has Yahweh as much delight in burnt offerings and sacrifices as in obeying the voice of Yahweh? Behold, to obey is better than sacrifice, and to heed than the fat of rams. For rebellion is as the sin of divination, and insubordination is as iniquity and idolatry. Because you have rejected the word of Yahweh, He has also rejected you from being king.”

Now, there are lots of words in here that would be tempting to study. You could go crazy looking up words like “obey,” “sacrifice,” “sin,” “iniquity,” “rebellion,” “idolatry,” etc. And certainly if there’s a word that you don’t understand or are not sure of its meaning, then that’s a good reason to study it. But in reality, when it comes to all these words, we actually learn far more about obedience and disobedience, sin, and sacrifice by studying the full passage than we would just by studying the individual words. It’s the passage itself–all these words put together into a related idea–that is most important and gives you more meaning that the words do by themselves.

With these big picture concepts in place, you’re much better equipped to bridge the language gap without inserting your own ideas into the text.

Pay attention to grammar

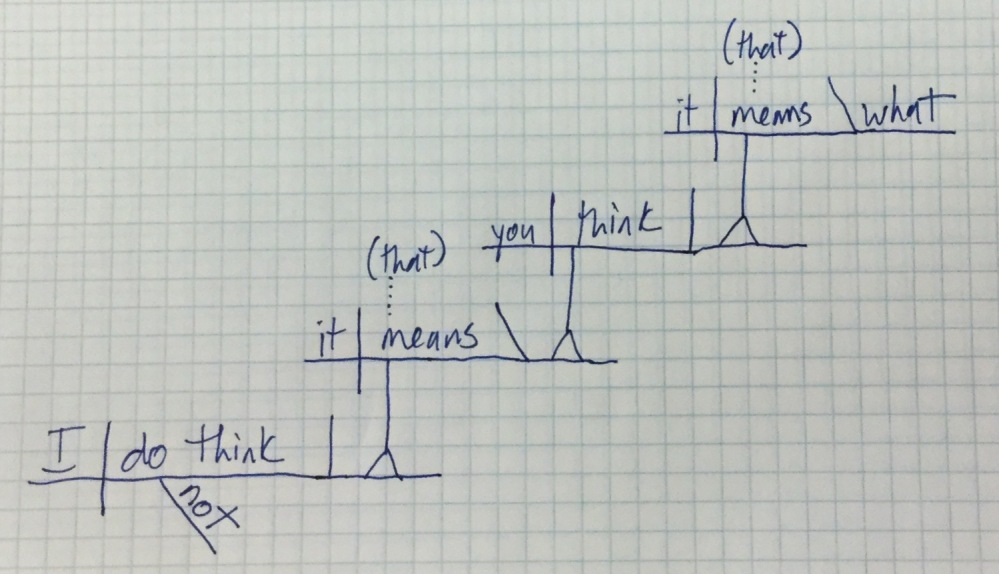

I know, I know. I heard the collective groan y’all just did when I said the word “grammar.” Unfortunately for you, grammar is pretty important when it comes to figuring out what the Bible means. Words, after all, aren’t free agents. They work together in a passage to produce meaning. If you’re going to accurately understand that meaning, you have to be able to understand how it’s all put together. That means knowing the difference between nouns and verbs, adjectives and adverbs. It means understanding what a preposition is and how a conjunction works. These are the building blocks of grammar.

In addition to that, you might want to brush up on how syntax works as well. What is syntax? It’s the way various parts of a sentence work together to create meaning. It refers to things like a subject, object, predicate, as well as things like a relative clause and a purpose clause. It’s grammar applied in context.

As it turns out, grammatical analysis is one of the most significant parts of the “observation” portion of Bible study. When you open up your text, your goal is to note everything you can about the passage. What’s the subject and what’s the verb? What’s the direct and/or indirect object? How are the prepositions working and what do they modify? What about participles and infinitives? How are they functioning? How are the conjunctions being used to glue the different ideas together? All these questions form the observations you make which will then lead into the next step in Bible study when you use this data to begin to interpret the passage.

Summary and resources

Language impacts meaning greatly! The words used and the ways they are used in language all affect meaning. You don’t have to be a language scholar to the study the Bible, but you do need to understand a little about how language words. And you need to have the drive to be proactive and bridge the language gap.

You’re not alone in this process! There are lots of study tools and resources the help. Here’s a few books and resources to help you in the process.

Books on Bible Study

- Hendricks, Howard G., and William D. Hendricks. Living by the Book: The Art and Science of Reading the Bible. Chicago: Moody Press, 2007. This is a classic layperson’s guide to doing self-guided, inductive Bible study and the popularizer of the well-known “observation–interpretation–application” approach to Bible study. 400 pages.

- Zuck, Roy B. Basic Bible Interpretation: A Practical Guide to Discovering Biblical Truth. Colorado Springs, CO: Victor, 1991. Another classic guide to interpreting the Bible filled with good discussions on many issues and lots of practical examples. 324 pages.

- Duvall, J. Scott, and J. Daniel Hays. Grasping God’s Word: A Hands-On Approach to Reading, Interpreting, and Applying the Bible. 4th ed. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2020. A great resource to have for reading and interpreting the Bible. There’s also a workbook available. 529 pages.

Bible Study Tools

- Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible. For doing word studies. Make sure to get one that matches the English translation you’re using.

- Vine, W. E. An Expository Dictionary of Old and New Testament Words. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 2003. A valuable tool for doing word studies.

Last But Not Least

Not everyone wants to or has the time to learn a biblical language. But just because you’re not a pastor or a Bible scholar doesn’t mean it’s not worth the effort. If you have the means to learn Greek or Hebrew and the drive to do it, jump in and start! If this applies to you, there’s a few books out there that can help you get started:

- Silzer, Peter James, and Thomas John Finley. How Biblical Languages Work: A Student’s Guide to Learning Hebrew and Greek. Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2004. A fantastic introduction to the biblical languages. This is a guide not so much for learning Greek or Hebrew but for understanding how to use Greek and Hebrew in Bible study by focusing on the similarities between those languages and how English works. 288 pages.

- Pratico, Gary D., and Miles V. Van Pelt. Basics of Biblical Hebrew Grammar. 3rd ed. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2019. The most popular basic Hebrew grammar used for learning Hebrew in seminaries around the country. This is a full Hebrew grammar designed to teach one how to read and translate biblical Hebrew. There’s also a workbook available for practicing concepts. 528 pages.

- Mounce, William D. Basics of Biblical Greek Grammar. 4th ed. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2019. The NT Greek companion to Pratico and Van Pelt on Hebrew. Used by thousands of seminary students and pastors to learn biblical Greek. Also comes available with a workbook for practicing concepts. 544 pages.