The Gospel Truth

- Nathan Schneider

As a pastor and a student of the Bible, my bookshelves are filled with all sorts of volumes and resources related to biblical studies. Some are thick, heavy theology books, others are paperbacks devoted to specific topics on issues ranging from God to counseling. I have a large section of reference works on Greek and Hebrew as well as Old and New Testament studies. But by far, the largest “collection” of books I have in my library are commentaries. If you don’t know what a commentary is, it’s a book (usually authored by a noted theologian, scholar, or pastor, depending on the purpose of the commentary) that offers an interpretation of a biblical text. Some commentaries get pretty detailed, diving into grammar and syntax, textual criticism, and historical discussions. Others offer a more theological or expositional approach, while some aim to help preachers shape their messages by giving big picture views of the passages along with helpful preaching outlines, illustrations, and applications. They are essentially full-length versions of the notes you’d find at the bottom of your average study Bible, but more comprehensive in scope.

Us pastors love our commentaries, and I don’t know any seminary student who hasn’t roamed the basement of the seminary library staring at all the commentaries on the shelves, making lists of volumes to collect in the years after graduation. In fact, that was a favorite pastime of mine while I was in seminary. The basement of the TMS library was a gigantic maze of bookshelves covering floor to ceiling, and the commentary section went on aisle and aisle. And it just so happened that as I was wandering through the library one day, perusing the commentaries and trying (unsuccessfully) not to break the tenth commandment, I came across the title of one commentary that made me stop and read it again in quizzical study. The commentary was titled, A Critical Edition of Q by James Robinson, Paul Hoffman, and John Kloppenborg, a volume from the well-known and notoriously liberal Hermeneia series.

Now, what was confusing about this commentary wasn’t the title, but the very subject the title represented. If you’ve never heard of the biblical book of “Q” before, there’s a very simple explanation for that…it doesn’t exist. Without getting too much into the historical and theological weeds, Q is a “document” that was surmised to have been the source for all the passages in the gospels of Matthew and Luke that don’t appear in Mark. It was supposed that anything that appeared in Matthew, Mark, and Luke was simply copied from Mark. But those passages that didn’t appear in Mark but in the other two had to come from a different source—this mysterious Q document.

From the early church all the way up to the Enlightenment in the late 1700s and early 1800s, it was generally held that the authors of the four gospels wrote their books independent of each other, and that Matthew was the first of the gospels to be written. It wasn’t until rationalism and Enlightenment philosophy made its way into biblical scholarship that this basic historical perspective become challenged. It started, along with a lot of other theological mischief, in Germany. Baruch Spinoza, a German rationalist and pantheist, is considered the “father” of the critical methodologies that would eventually mark Christian liberalism for the next three century. He saw the plain meaning of the biblical text as the source of negative effects on people and society, and so he began to shift the focus of biblical scholarship away from the text of Scripture, instead focusing attention on the history of the text. The results have been devastating. As David Dungan comments,

In short, the net effect of what historical critics have accomplished during the past three hundred years . . . has been to eviscerate the Bible’s core religious beliefs and moral values, preventing the Bible from questioning the political and economic beliefs of the new bourgeois class. . . . Having cast the traditional status of the Bible overboard, the modern historical critic is left with a giant hermeneutical vacuum, into which this divinely gifted, rational interpreter is free to project any meaning he or she wishes, bound only by one’s physical sense experience (David Dungan, A History of the Synoptic Problem, 361).

In other words, historical criticism has shifted everyone’s attention away from the intended meaning of the biblical text and placed it on how we got the biblical text in the first place. Having accomplished this shift, the Bible becomes simply a source for subjective meaning…a meaning that no longer challenges the philosophies and morality of the social elites.

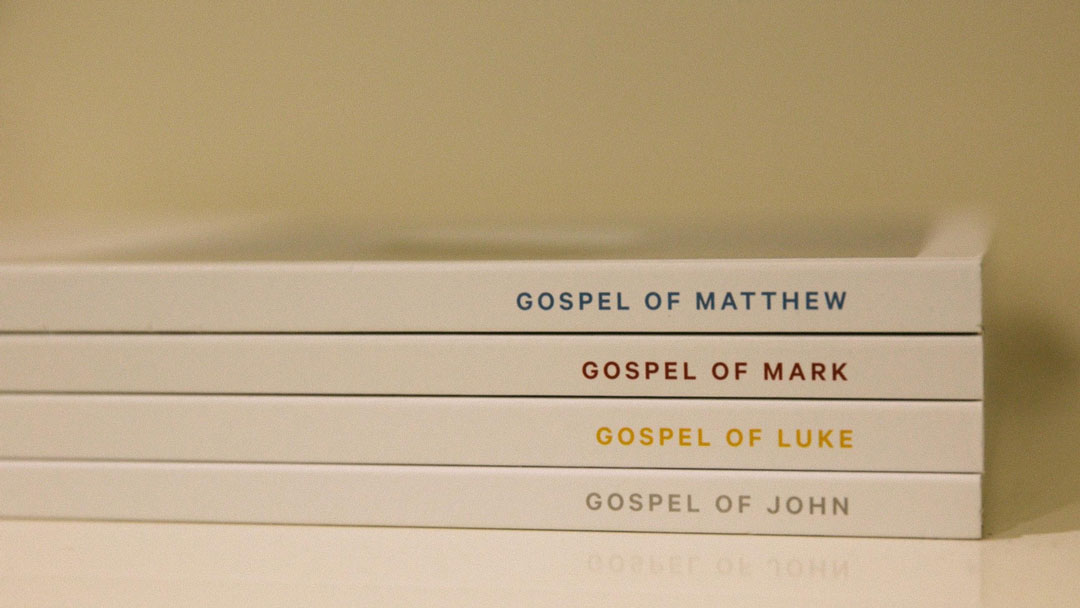

Numerous areas of the Bible came into the historical-critical crosshairs. Julius Wellhausen launched an all-out assault on the Pentateuch with the overarching goal of denying Moses as the author (and thus destroying the very theological foundation of Judaism and Christianity). The books of Isaiah and Daniel received similar treatment because of their strikingly accurate prophetic records (e.g., Isaiah 44:28–45:1; Dan. 11:1ff). In the New Testament, several epistles came under critical scrutiny, including Ephesians and 2 Peter. But by far, the gospels were ground zero for the most ferocious of critical assaults for the obvious reason that these four books purport to be eye-witness accounts of the life and ministry of Jesus Christ. And just like the biblical text, the aim of critical gospel studies became searching for the true historical Jesus. If that phrase—”historical Jesus”—doesn’t sit well with you, that’s good, because it shouldn’t. And that’s because there’s an underlying assumption behind it. Searching for the historical Jesus assumes that the Jesus who existed in history is different from the biblical Jesus who is portrayed in the gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. In other words, the critical approach to the gospels is built on an inherent distrust in the historical accuracy of the gospel accounts.

In particular, Matthew, Mark, and Luke stood out. John is such a different gospel account that it wasn’t really part of the discussion. But the other three share a surprising amount of material in common, so much so that the way these three gospels related to each other and how they came to be written became known in scholarly circles as the “synoptic gospel problem.” Now, as I already indicated, this wasn’t really a problem for the first 1800 years of church history. It was taken as gospel (sorry, couldn’t help it!) that Matthew wrote his gospel account first, and that Mark and Luke wrote independently of Matthew and each other. Now, part of this is based on the Old Testament principle that all judicial conclusions be made on the basis of two or three witnesses (Num. 35:20; Deut. 17:6; 19:15). God went beyond that and gave four witnesses, each independent of the others.

Now, within the church there has been some healthy debate over the requirement that we assume there was no contact or interaction between the gospel writers. After all, Luke himself admits to writing his gospel record only after following “all things closely for some time past” (Luke 1:3). I think we can allow for the fact that Luke may have had access to Matthew’s gospel, though it’s hard to prove it and it’s not necessarily required.

But the historical critics went beyond these measures. What they aimed to do was bring into question the supernatural origin of Scripture. Thus, Moses didn’t receive Torah via inspiration, but rather the Pentateuch was pieced together over hundreds of years using four different religious traditions ranging from pre-Israelite to post-Babylonian exile. Daniel and Isaiah couldn’t have actually prophesied of future events. These had to be prophesy “after the event.” And the gospel writers couldn’t have come up with four complementary and harmonizing records of the life of Jesus. One person had to write their gospel, and the others simply copied from him. As Dungan remarks, “It is striking to see the underlying modern historical assumptions just taken for granted—that these authors all wrote in an entirely human fashion. There is no mention of divine inspiration anywhere” (322).

This is where the gospel of Mark comes in. Mark became the perfect “first gospel” for historical critics, and for a number of reasons. The first was a political one. These scholars in Germany wanted to free themselves from Roman Catholic influence and authority, and so Mark provided a convenient book on which to base their theory because it doesn’t allow for the glorification of Peter the way the Roman Catholic church was able to wield the gospel of Matthew.

The second reason Mark found its way into the limelight in critical studies was because it lacked the numerous “supernatural events” (i.e., the virgin birth visit of the angles, the star of Bethlehem, the resurrection of Jesus) that are included in Matthew and Luke. Remember, rationalism is inherently antisupernatural. In fact, what historical critical scholars aimed to do by getting “behind the text” was to explain the seemingly “supernatural” events of the text in rational terms. Thus, while the biblical writers might have thought something extraordinary that happened was due to God’s activity, in reality we “know” now because of modern science that these events have a perfectly natural explanation.

But there’s another reason Mark was such a useful gospel for critical scholarship: it was simple. It was short. And thus, is fit perfectly with the burgeoning theory of evolution that was sweeping the scientific world and kicking down doors into other areas of study outside of biology. Evolution functions based on the assumption that things naturally move from simple to more complex. Charles Darwin applied that assumption specifically to the field of biology, but others took that underlying principle and used it in all sorts of other disciples, including sociology, anthropology, and religion. Thus, Mark—the simplest, shortest, and least complex gospel of the four—fit the mold of modern evolutionary thought. Being the earliest, it was the more historically reliable gospel. I say “more” reliable, because these modern scholars never put full confidence in any of the gospels for historical reliability. It just fit the paradigm that Mark, being the earliest of the gospels and thus the closest to the actual events, would be more reliable than the others which came later. And just like it was assumed that the simplest of organisms eventually gained genetic complexity and led to the formation of more complex life forms, so the simplest gospel became the source for the later and longer and more theologically “complex” gospels.

But this didn’t completely solve the “synoptic gospel problem.” After all, if Matthew and Luke used Mark as a literary source to write their own gospel accounts, then how do we explain where they got their extra material? Thus enters Q, the proposed document that accounted for all this extra material. It has to be said at the outset that Q is a document that has never been found. No one has ever seen a copy of it. It exists only in the imagination of scholars who assume that Matthew and Luke could not have come up with their gospels without it.

Which leads to this question: How can someone write a commentary on a document they’ve never seen? How do they know it even existed if it’s never been found? Welcome to the world of the circular confirmation bias of theological liberalism, where you know Q existed because Matthew and Luke used it, and I know they used it because how else did they write it? In other words, this commentary I saw on the shelf in the dungeons of the TMS library was the product of three centuries of scholarly hubris and assumption. In the name of “science,” they did perhaps the least scientific thing imaginable—they wrote a commentary on a book they’ve never seen.

Randy Karlberg and I were talking the other day and he shared with me a little anecdote of when he discussed this topic with a group of high schoolers some years back, who were absolutely baffled at how anyone could come up with the idea of a supposed document behind the gospels that no one’s ever seen but we absolutely know it exists. To them it was the height of “crazy.” When Randy said that, what instantly popped into my head was this: sometimes it takes a Ph.D. to prove to the world just how uneducated someone can be. And in contrast, as the psalmist says, “I have more understanding than all my teachers, for your testimonies are my meditations” (Ps. 119:99). In this case, a group of high schoolers were more well grounded, reasonable, and—dare I say—rational—than the “great” rationalists who developed these theories which have done so much to assault Scripture, inerrancy, and the historical reliability of the Bible.

Is it just that, as Paul was accused of, “your great learning is driving you out of your mind” (Acts 26:24)? I don’t think it’s that simple. Of course, there’s always the temptation within theological scholarship to abandon Christian orthodoxy in order to gain scholarly credibility. There’s no doubt that the majority of higher educational institutions would laugh in the face of someone who wanted to write their doctoral dissertation on the independence theory of the four gospels. But I think there’s something deeper and more nefarious at play here. What keeps showing up again and again in these kinds of scholarly works is an antisupernatural, anti-inspiration approach to the Bible. There is a desire to avoid the text of the Bible and the accountability it brings because of what it says. It is anti-biblical defiance that is at work, and the great spirit of the age—the spirit of rationalism along with the spirit of postmodernism and post-structuralism—all posture themselves as philosophies which aim to have the Bible say anything other than the plain sense of the text.

And in that sense, if you’re going to commit yourself to the Bible, and follow what it says, and approach it as a supernatural book, written under divine inspiration, a book of perfect historical accuracy, without any error of any kind, and never able to lead someone into error—all the elements of classic inerrancy and infallibility—then you are taking a road on which you’re going to constantly walk against the flow of everyone around you. The entire world is traveling in the opposite direction, and you’re in the way. You’re in the way not just because you view the Bible differently than they do. You’re in the way because the meaning you draw from the text directly implicates them and calls them to account for their life and practice. You are assaulting the system they’ve put up to protect themselves from what the Bible says. You’re deconstructing their safe house, where they feel secured against the moral demands of a Jesus who really existed and really did all the things the four gospels said that he did.

But at least we have something going for us that they don’t . . . the book we follow actually exists, and we can hold it in our hands, and we can read it, and we can study it. Some call biblical Christianity “blind faith.” Well, I’ll take that kind of faith any day over the faith that would write a $100 commentary on a document that doesn’t exist. Just saying.